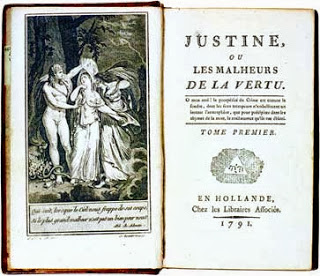

Historically, erotic art (visual and textual) was produced primarily for men, by men. Yes, there have been exceptions, but the ones that survive are rare. It was only in the 20th century, and mostly in the latter part, that women began to produce erotic fiction aimed at women. This has been portrayed as emancipatory and, unarguably, it is. It filled a vast and silent gulf. For millennia we have known what men wanted, what they fantasize about, what arouses them. In a recent conversation on Facebook about Fifty Shades of Grey, Kristina Lloyd commented:

I think the reason the book spoke to so many women is because precious little else in our culture does when we’re talking het female desire. Give a bone(r) to someone starving, and they’ll pounce on it. The success of the book is about the failures in our culture. I wish we could chart a similar moment when it was suddenly acceptable for men to access and enjoy adult material without recrimination. 1970s? 18thC? Forever? 1

Once a book has sold 100 million copies, this is a pretty definitive sign that it has become acceptable, in the mainstream, for women to access material that arouses them. 2

It isn’t accidental that, since the 1960s, as the production and consumption of erotic material aimed at women gained momentum, so has the criticism of how women are presented in male-centered erotic material. It is only when both flavours are readily available that one can see the differences between them. In the past 50 years, feminists have raged against the objectification of women as objects of desire. We are more than the statues, the Madonnas, the Whores, the bountiful breasts and the warm wet holes you make of us. We’re not just breeding stock, or somewhere to put your cock. We are not that simple. See us – desire us – for what we truly are, instead of the facile, two-dimensional caricatures you’ve made of us! It was a legitimate demand.

Who would have thought that, suffering as we have from this diminishment, we would in turn come to produce material that commits the same sin? Yet, from the heady days of the explicit bodice busters until now, we have, with some laudable exceptions, fallen into the same trap. The spectre of the inscrutable Alpha male, with his money and his power, and his somewhat-but-not-impossibly-large-cock, his insatiable sexual appetite, his obsessive desire to please only the heroine and – by extension – us, has dominated the world of female-centred heterosexual erotic content. Christian Grey is its poster-boy, but his clones are everywhere. And, quietly, they always were. Consider Mister Darcy.

And there is little sympathy for the few male voices that speak up to complain about it. Partially for the same reason that very few women in earlier eras spoke up against female objectification; we are torn between our need to be known for who we are and our desire to be desired, even if imperfectly. Moreover, and like many women through the ages, men have participated greatly in their own objectification. It does seem a little whiny, after two thousand years of Venus De Milo, to complain that being simplified as a brainless, lust driven cock with a wallet is unfair.

But a few men have spoken up. Like their counterparts, they speak in the language of their own desire. Don’t we all? Nonetheless, the subtext is clear: please don’t make me a caricature. After trying his damnedest to get through volume one of Fifty Shades of Grey, my friend and sometimes co-writer, Alex Sharp, has recently written a piece I think every female erotic writer who sets out to craft male characters – especially the non-vanilla variety – should read: “I am he, and he is me.”

Good fiction writing embraces realism, even in its most dramatic flights of fancy. And, in my opinion, well-written erotica should attempt to embrace the eroticism in the entirety of the character or, at least, attempt an honest fictionalization of the problems of desire and objectification. I think that is the challenge that separates erotic fiction from pornography.

Admittedly, I’m torn. Desiring someone in all their complexity is a laudable aspiration, but I have several well-supported doubts as to whether, in the moment that lust takes us, this is even possible. Perhaps it is only now, with all our objects of desire so flagrantly on display, that we can begin to come to terms with the dilemma that so haunted Kant, the schism between desire and full knowledge of another. Jacques Lacan said that there is no ‘sexual relationship’; our projected desires are the product of the symbolic, muted world of controlled meaning that bears little relation to the real humans upon whom we heap our fantasies. Being a romantic, despite himself, he felt that only in love, in the terrifying Real of love, could we hope to overcome the watery barrier of symbolism and step out of Plato’s cave and into the blinding light of day. 3

So love in erotic writing should be the answer, right? Lord knows, the genre of erotic romance has well and truly eclipsed the erotica genre. It has all but swallowed it up, in no small part because Fifty Shades of Grey was marketed as erotica rather than romance. A large proportion of those 100 million sales have been to women who’d never read ‘erotica’ before. Now each time they pick up an erotica novel, they’re expecting romance.

The quandary, as I see it, is that love itself has been objectified. The very presence of the inevitable happy ending diminishes and even denies the terrifying truth of love: that it is seldom forever, that – like everything else – it changes, that its very volatility and instability is what makes it a dangerous place but also one of greater knowledge.

I’ve often contemplated the Judeo-Christian myth of the Garden of Eden, so often used as a metaphor for a state of perfect love. Its portrayal of humanity in a state of innocence, nakedness, and openness, before we ate from the tree of bitter knowledge, offers us an aspirational but ultimately impossible and fantasmatic vision of love. And I’d argue that most fictional romance presents this state as the final one; the scene fades on Adam and Eve, in all their natural glory, hand in hand in the garden of delight.

But isn’t love is more fittingly portrayed as the Expulsion from the Garden? That fruit we tasted was not only the knowledge of good and evil; it was the knowledge of ourselves and of each other. Love is the struggle to keep holding hands while carrying the burden of that knowledge on our backs. Assuredly, it has its idyllic aspects, but it also takes us through the rocky desolation of T.S. Eliot’s Wasteland. If we are to truly know each other, we must work to find erotic love in that dark and sometimes barren place as well.

So, I want to challenge you, as fellow writers of erotica, to try to forge the erotic there in that far more realistic landscape. We’ve spent too long in the garden; time to get out into the real world.

1 Lloyd, K. (2014) Comment in response to ‘I’ve Just Watched The FSOG Trailer’ Facebook post. Accessed 3 August, 2014 https://www.facebook.com/Remittancegirl/posts/10203583569204376?comment_id=10203584398105098&offset=0&total_comments=57↩

2 Flood, A. (2014) Fifty Shades of Grey Trilogy Has Sold 100m worldwide, The Guardian Online. Accessed 3 August, 2014 http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/feb/27/fifty-shades-of-grey-book-100m-sales↩

3 Lacan, J. (1988). On Feminine Sexuality: The Limits of Love and Knowledge: Book XX, Encore 1972-1973. (B. Fink, Trans., J. Miller, Ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Company.↩