My post last month “The Club” garnered this clear-eyed response from Lisabet Sarai:

“Most readers, however, choose erotica because they want to feel, not because they want to think. Specifically, they want to feel good–aroused, satisfied, reassured, or like they’re getting away with things they’d never attempt in the real world. To these readers, the deeper issues that concern you are close to irrelevant. Indeed, to many of them, craft and linguistic grace matters little if at all.“

She is, of course, absolutely right about this. The vast majority of contemporary readers come to the erotica genre to “feel good–aroused, satisfied, reassured,” most consider the themes that drive me to write “close to irrelevant” and don’t give a shit about “craft and linguistic grace.”

Many years ago, I was in the music business; I sang in a band. We got a record contract with a big company who then decided our music was too ‘alternative’ and pressured us into writing more commercially accessible music. I wanted to be loved so much. I wanted to be successful so badly. I thought it was the only thing in the world that mattered to me; that adulation. But even at the time, I knew I was betraying myself. Somewhere inside me, even as we made the changes they insisted would make us famous, I knew I was doing the wrong thing. I did it anyway.

It’s a term I don’t like and rarely use, but since I am speaking of myself alone, I feel justified in saying I whored myself for approbation. And the fact that you haven’t got a clue what band I was in or what the music was like is proof of the fact that my choice to compromise my artistic vision was not a wise one. Had I stood my ground and refused to write more ‘commercial’ music you might still never have heard my work, but at least I would have kept my integrity. In the end, you can only account for your own choices.

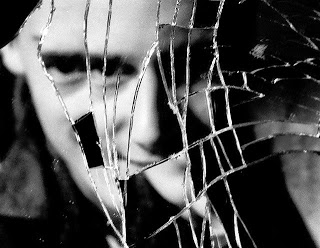

I had something of a mental breakdown after that experience and, when I recovered, I swore that I’d never choose the lure of commercial success over artistic integrity again. Not because writing pop music is demeaning or requires less skill, but because it was a totally inauthentic act for me. For some people, producing accessible work is exactly what they want to do. And they do it well. They deserve the success they get because they’re not faking it, they’re not putting on the breaks of their intellect or dumbing down their ideas. They genuinely believe in the product they produce, and it shows.

I have never wanted to produce writing that facilitated masturbation, or made people feel safe and satisfied and reassured. Although I would be happy in knowing something I wrote might have turned someone on enough to help them to orgasm, I definitely have never been interested in making a reader comfortable in any way.

I remember many years ago having a drink with the lovely Lisabet in a bar in the Far Sast and saying: “Not only don’t I want to write this stuff, but I don’t think I can even do it.” It’s not easy to do. I don’t want you to think that I believe that conforming to current reader expectations in the erotica genre is easy. Far from it. I literally have not got the skills or the drive to do it. But more importantly, I don’t have the passion for it. I don’t want to produce cultural work I would not feel proud about publishing. I don’t want to write what I’m not interested in reading.

I believe that this has been coming for a while. The immense rise in popularity of erotic romance, its eclipse of the genre, and the sensational success of Fifty Shades of Grey has literally redefined the genre of erotica. It has led readers to expect something wholly different from what I can or am interested in producing.

For this reason, I think it is futile to continue to fight a battle that can’t be won. It’s an absurd fight and I should have realized this a long time ago. Moreover, I find myself in cast in the role of some stern, arrogant and, ironically, old-fashioned harridan in this debate. I feel like a crazy old Marxist with long, greasy grey hair who smells of body odor and cat piss, who stands on the corner of Oxford Street, screaming unintelligible gibberish at people who walk by, wrinkle their nose and go back to texting on their mobile phones. I am, in this genre, an irrelevance.

As Anais Nin said in the quote above, “we don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.” And I am no longer an Erotica Reader and Writer. Time to move on. This is my last post on the ERWA blog. It has been a wonderful experience sharing this virtual space with all these talented writers and adventurous readers. I wish you all the very best.

Good night and good luck.