|

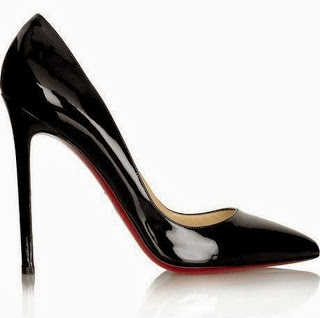

| If we wore these everyday, no one would think they were sexy. |

The term ‘normalization’ (and the verb ‘to normalize) has become very popular of late. It has a number of meanings, but its most current use in the media refers to a process by which exposure to something renders it ‘normal’ in the minds of those who are exposed. For instance, it has been proposed that the preponderance of photos of women’s legs, showing them with a gap between their thighs has ‘normalized’ a body type that is not normal (Jones, 2013), and video games ‘normalize’ violence against animals (Hochschartner, 2013).

Of course, we’ve spent years hearing about the way pornography – any kind of pornography – normalizes the view of women as sexual objects and encourages violence against them (Horeck, Days, & Don, 2013). Attempts to verify this through research have resulted either in highly ambiguous results, or actually contradicted these claims. A literature review of a large number of studies has concluded that porn is not even a co-relational factor in violence against women (Ferguson, 2013). In fact, there is good data to suggest the opposite; that the more widespread the access to pornography, the lower the violence to women (Amato & Law, n.d.).

As of January, 2014, it will be illegal in the UK to possess material that contains eroticized depictions of rape. Not possession of photographs or videos of actual rape – that was always illegal, but material containing fictional depictions of rape (Zara, 2013). According to many sources, including the Prime Minister, David Cameron, exposure to this kind of pornography ‘normalizes’ sexual violence against women (Morris, 2103).

My problem with the word ‘normalize’ is that it has been widely interpreted to mean that exposure to whatever it is that is currently offensive to us will cause us to think that it’s okay. They’ll stop having negative feelings about it, and embrace it as part of their everyday lives. I’m not disputing that constant exposure to something will change the way we think about it – that would be cognitively impossible for that not to occur. What I’m disputing is our assumptions about two things.

The first is a widespread assumption that fictionalized versions of horrific realities are interpreted by the brain in the same way as witnessing or experiencing those realities. I can accept, for instance, that small children might have difficulties telling the difference between a fictionalized, mediated version of war and war itself. But adults reading “War and Peace” or watching “Saving Private Ryan” don’t believe they are actually experiencing war. Admittedly, we do suspend disbelief when we read or view fiction, but we don’t mistake it for reality.

The second assumption is that repeated exposure to mediated forms of real horrors will cause us to feel neutral or even positively about them. This has no basis in fact either. Indeed, in the last century, we have been exposed to more mediated versions of reality than in the whole of human history. More war, more death, more rape, more everything. And as much as the media would like you to believe you live in a terribly dangerous time, the truth is that we are safer, healthier and longer-lived than we have ever been.

As a woman, a writer of erotic fiction and a questioner of received wisdom, I do believe that the widespread availability of explicit sexual imagery must, indeed, be having some effect on us. I just don’t accept that it is either wholly positive or wholly negative. For instance, I’m pretty sure that far fewer people today feel that there is anything fundamentally evil about sex; I think porn has played a part in this. I think the quantity of mediated sex out there has allowed many more people to admit to watching and enjoying it.

I also believe – although I have no hard evidence of this – porn has served to ‘model’ what sex should look like. After all, for many people, it’s the only sex they see (other than their own). And porn sex is, by its nature, exaggerated and dramatized. I think there are people who may (because they aren’t having the sort of sex that looks like the sex in porn) feel a greater sense of dissatisfaction with the sex they do have.

In the Middle Ages, children learned what normal sex looked like by witnessing it – either seeing it, or hearing it in a darkened room because private space was at a premium. Today we’d call that child abuse. These days, other than porn, the only way to see real sex between real people is by being a voyeur, which is loaded with its own taboos. It’s hardly a wonder that amateur porn became so popular. There is some sense that this is real sex. Sadly, because of the fact that it needs to stand up against produced porn, more and more commercial porn memes creep into amateur porn. Conversely, commercial porn producers have sought to make their product look more ‘amateur’ in order to appeal to amateur porn viewers. They tend to fail miserably.

What I’d really like to dig my inquisitional fingers into is the idea of ‘normalization’ as it applies to the erotic. I want to make a distinction between the sexual and the erotic, because I am increasingly coming to believe that there is the biological urge to scratch the itch, which requires nothing other than a relatively functional body and no imagery or semiotics at all, and something else. This something else is the intersection between that biological imperative and language. Not language in the sense of words, but language in the sense that, as our brains mature, we process reality through the veil of language. There is nothing fundamentally sexy about a black, patent leather, high-heeled shoe. It is language in the larger sense, in the way we make relational linkages and chunk feeling and meaning together, that has made the ‘fuck-me-pump’ the iconically sexy item it has become.

I’m going to call this ‘the erotic’ as distinct from ‘the sexual.’ The erotic is heavily dependent on limits: on what is allowed and what is forbidden (Bataille, 1962; Foucault, 1980; Paz, 1995). There is a reason for why the adjectives we use about the erotic ideas that turn us on are negative: naughty, filthy, dirty, forbidden, nasty, sinful, obscene, perverse, wanton, illicit, etc. We want, most passionately, the things we shouldn’t want. It doesn’t mean that we act to get them, or need to transgress socially accepted behaviour in order to be sexually satisfied, but our mind goes there. Of course, positive things can also be erotic: beauty, love, devotion, affection, perfection, purity, faith, truth… but even as I type these words, and even as you read them, it starts to become obvious that erotic desire feeds more voraciously off the forbidden than the allowed.

Here’s the paradox: things that become ‘normalized’ can no longer be the stuff of erotic fantasy. So, I’m not arguing that normalization doesn’t occur. I’m suggesting that it is a self-limiting phenomenon. I’m suggesting that we are twisted little creatures who don’t get off on the ‘normalized’. And so our fears as to its consequences may be somewhat hyperbolic.

My greatest antipathy towards the ‘normalization’ of the erotically forbidden is that it will lose its power to be erotic. I believe that our inner, transgressive, politically incorrect and ugly erotic desires are part of who we are as human beings. Our ability to understand that these things we want, things that when acted out in the real world would be atrocities, are part of the mechanism that preserves our inner and outer worlds as separate. Like fantasy, fictionality affords us a playground for our deeply unsocial selves. It doesn’t school us in what is acceptable in the real world. It underscores and helps to contrast between the two.

References

- Bataille, G. (1962). Death and sensuality: A study of Eroticism and the Taboo. New York: Walker and Company.

- D’Amato, A. (2006). Porn Up, Rape Down. Northwestern University School of Law: Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper Series, 1–6. Retrieved from http://anthonydamato.law.northwestern.edu/adobefiles/porn.pdf

- Ferguson, C. J. (2013). Pornography. In Adolescents, Crime, and the Media: A Critical Analysis, Advancing Responsible Adolescent Development (pp. 141–158). New York, NY: Springer New York. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6741-0

- Foucault, M. (1980). A Preface to Transgression. In Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews (pp. 29–52). Cornell University Press.

- Hochschartner, J. (2013, November 29). Video Games Normalize Animal Cruelty. Retrieved December 8, 2013, from Counterpunch.org: http://www.counterpunch.org/2013/11/29/video-games-normalize-animal-cruelty/

- Horeck, T., Days, S., & Don, B. (2013). Public rape: representing violation in fiction and film. Routledge.

- Jones, A. (2013, November 22). Sexualization Thing Gap Retrieved December 8, 2013, from TheWire.com: http://www.thewire.com/culture/2013/11/sexualization-thigh-gap/355434/

- Morris, C. (2103, November 17). ‘Rape porn’ possession to be punished by three years in jail, David Cameron to announce. Retrieved December 8, 2013, from Metro.co.uk: http://metro.co.uk/2013/11/17/rape-porn-possession-to-be-punished-by-three-years-in-jail-david-cameron-to-announce-4189512/

- Paz, O. (1995). The double flame: love and eroticism (p. 84). New York: Harcourt Brace. Retrieved from http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=AeKEAAAAIAA

- Zara, C. (2013, November 18). Rape Porn Ban Comes To UK: Possession Of Images Depicting Simulated Rape To Be Punishable By Jail. Retrieved December 8, 2013, from International Business Times: http://www.ibtimes.com/rape-porn-ban-comes-uk-possession-images-depicting-simulated-rape-be-punishable-jail-1474952