I’ve been considering the genre of erotica in historical context as a way to understand where it came from and what it has become. From a European perspective, it seems fair to begin with the Greco-Roman poetry of Sappho, Ovid, Juvenal and the Dionysian spectacle of the Satyr Plays (of which we no longer have any clear records). But we have a problem: it is almost impossible for us today to truly grasp what kind of a relationship the ancient Greeks and Romans had with sex. Judeo-Christianity and, later, the Enlightenment and rise of rationalism have had profound effects on the way we contextualize desire and sex both in relation to ourselves and to our society. We often represent the Greeks and the Romans as being a lawless bunch of reprobates, but this isn’t true. There were very strong prohibitions and social rules about how one conducted oneself as a sexual being and how that reflected on the overall character of a person. They were just very different from ours.

Boccaccio wrote the Decameron in the 12th Century – a collection of tales which borrowed mostly from earlier erotic folk stories as well as westernized oriental narratives. The Tale of Two Lovers, an epistolary novel of the 15th Century, was penned by a man who later became a pope. The Heptameron was written by Marguerite de Navarre in the 16th Century. All these writings are bawdy and explicit in their exploration of human sexual adventure. But it is also fair to say that they are not simply detailed descriptions of sex. To one extent or another, they all contain a good deal of humour and there is a considerable focus on the licentious behaviour of characters whose social status demanded they be modest. They were often about the secret sex lives of the rich and celibate. Eroticism, politics, and social satire it seems, went hand in hand.

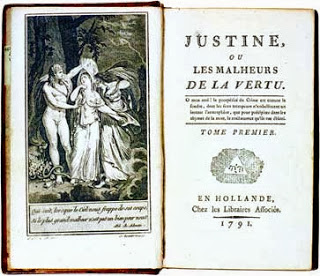

The libertine movement of the 15th and 16th centuries was an interesting evolution. Written by aristocrats for aristocrats, it represented the pursuit of pleasure as a radical philosophy in itself. Its comparison with earlier writings is interesting. For all its sexual excess, its humour is more curdled and jaded and, for all its explicitness, seems more aimed at offending sensibilities than representing the pleasures of the flesh. (It always reminds me of people desperately trying to fuck on way too much cocaine at four in the morning. Take my word for it, it’s not all that much fun.) Then we get to Sade,with his lists of debaucheries and his blatant attack on Catholic mores. These books are pornographic in the sense that they are explicit, but as Angela Carter pointed out, they are also aimed at honestly representing the almost unlimited power of the wealthy and the violent and dehumanizing use of the poor. Sadean writing may be erotica, but it is also heavy handed social critique.

The Victorian era saw a new age of confessional erotic writing. For the most part, there isn’t much obvious attempt at social commentary, other than the adolescent glee of writing explicitly about sex acts in a society that had developed an almost psychotic fear of discussing it in public. Certainly there was pleasure taken in writing and reading about what was socially forbidden. But it lacks the confrontational nature of earlier erotic writing.

Although I would include Sacher-Masoch’s Venus in Furs, it was not really until the 20th century that we see the use of erotic writing as a tool for exploring or defining the self in relation to society. In the works of Miller, Nin, Nabokov, and Duras, you begin to see erotic stories that have deeply psychoanalytical dimensions. They all, to some extent or another, pit the individual’s pursuit of erotic desire against the prevailing environment. As conscious, revolutionary acts of disobedience in pleasure. And yes, the sex matters and the sex is erotic, but it is also a private struggle for inner structure in the face of a confusing world.

I’d like to stop here and say that there has always been pornography, both visual and written, whose sole purpose was as an aide to sexual arousal. Certainly most of the Victorian works could not really be viewed as having other uses. And the sexually explicit pulp erotica of the 50s and 60s served the same purpose. But the literary and financial success of novels like Miller’s The Rosy Crucifixion trilogy, and Nabokov’s Ada or Ardor put pressure on writers in the 70s to add more explicit sex to their work in order to sell more books. It was no longer a revolutionary act to describe a sex scene in detail, it made monetary sense.

It is ironic that the genre we now call erotica hasn’t really been around that long. Until the early 70s, writers either considered they were writing pornography as a sex aid (and usually for the money) or they felt they were writing literature which, as a function of exploring the human condition, explored the characters erotic lives as well.

The post-modern literary world has, with the exception of some outstanding Queer writers, mostly portrayed graphic sex in their writing as a site of alienation. From Michel Houllebecq to Ian McEwan, it seems that authentic characters shouldn’t ever have good sex, or sex that informs them of anything other than the emptiness of the act. Intelligent people, it seems, have uniformly awful sex, according to the literary world.

So erotica, as we know it, is a genre that has tried to serve many interests. There are still writers and readers who see the job of erotica to simply provide stimulating imagery for masturbation or spicing up a couple’s sex life, but are uncomfortable with consuming what is clearly labeled pornography. There are also writers and readers who see erotica – particularly erotic romance – as a way of narrating romantic stories more realistically, including the sexual aspect of the evolving romantic relationship. And then there are those of us who feel that exploring the complex erotic desires and actions of characters continues to offer a landscape in which to reflect on the human condition as a whole.

It’s hardly a wonder that readers get disappointed when they pick up an erotica book and falls short of their expectations. As a society, we still feel the need to shove our written explorations of eroticism into a single, literary red-light district. It is a crowded little enclave, with many agendas.