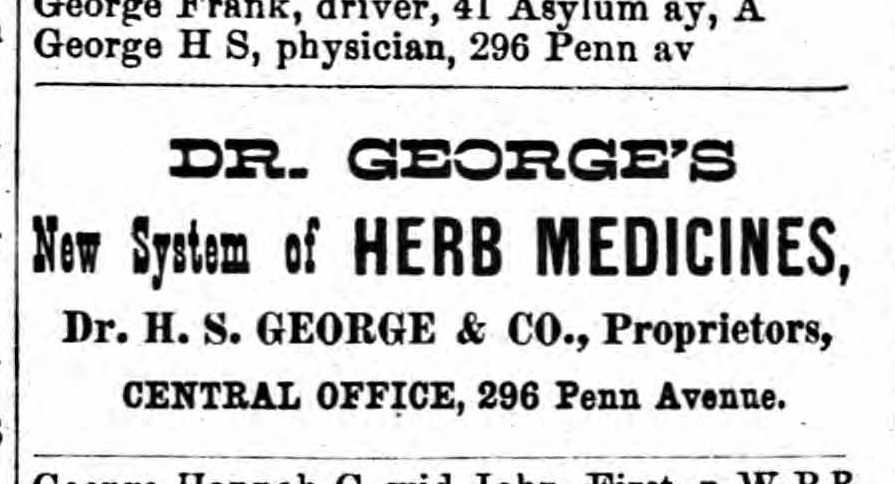

There is no better way to immerse yourself in the daily life of times past than reading a newspaper of a century ago over your morning tea. I’ve discussed the scandalous pleasures of perusing old newspapers in previous columns, but as the year-end holidays draw near, I wanted to offer you this special treat of a discovery from the 22 April 1913 edition of the York Dispatch (see page 2). And you thought no one in 1913 had any fun!

Professor C.U. Hoke’s mesmerizing vibrating fingers likely inspire a smile, but the testimonial by the lady who preferred not to be named in the newspaper–a true lady may only appear in the papers at her birth, marriage, and death—may even provoke a chuckle. Imagine the poor hotel keeper, clearly a widow, who was languishing in her bed with heart and female weakness. Fortunately, Prof. See-You-Hoax’s miraculous vibrating appliance handily restored her energy and her will to live. Results like these can be yours, too, but only with regular daily applications of the professor’s miracle cure.

Beyond the obvious hucksterism, I imagine most of us have heard the following story of the invention of the vibrator. Apparently Victorian doctors believed that the ubiquitous malady of hysteria in the female (basically discontentment with her social role) could be cured by genital massage to provoke hysterical paroxysms. In this story, both doctors and patients were innocent of any sexual element to the treatment and entirely ignorant of the existence of the female orgasm. Doctor and patient merely doggedly repeated the procedure during regular appointments. The suffering ladies attested that the treatment worked wonders for energy and mood, but the bored doctors started getting repetitive stress injuries in their hands. Fortunately, an inventor (Professor Hoke?) saved the day and physicians’ hands with his vibrating electrical device.

A movie was made with Hugh Dancy and Maggie Gyllenhaal called Hysteria (2011), which dramatizes this very tale, and if it’s in the movies, it must be true! Even better, the story apparently originated with a scholarly work entitled The Technology of Orgasm by Rachel Maines (1999). The book won two academic prizes.

Maines’ discovery caught fire with the public. And it is a good story.

However, according to Robinson Meyer and Ashley Fetters in the Atlantic’s “Victorian-Era Orgasms and the Crisis of Peer Review” (6 Sep 2018), the vibrator origin story isn’t true. Scholars Hallie Lieberman and Eric Schatzberg determined that “[m]anual massage of female genitals was never a routine medical treatment for hysteria.” These later scholars found that Maines provided no real evidential support in her book. The citations simply don’t lead to her conclusion. Maines herself now contends that, “I never claimed to have evidence that this was really the case.” She expected immediate pushback to her “hypothesis,” but claims she was surprised it took this long. “It was ripe to be turned into mythology somehow,” she said. Her goal, Maines said, was to get people thinking and talking about “orgasmic mutuality.” (“Victorian-Era Orgasms”)

The encouragement of a discussion of orgasmic mutuality is to be applauded. However, perhaps Maines could have been more straightforward in her presentation of the evidence in a scholarly context. She was obviously right that the story was ripe to be mythologized.

The Atlantic article also uses this case to show that academic presses don’t really fact-check, but instead rely on peer review. Perhaps the reviewers were so enchanted with the fantasy of doctor-induced paroxysms, their critical faculties were mesmerized into blissful credulity?

In any event, if you’re at a holiday cocktail party in person or on Zoom in the coming months, and someone so happens to regale you with this history of the invention of the vibrator, you can set them straight. It’s nothing but a fanciful tale. That leaves us erotica writers a lot of space to make up our own vibrator origin stories. The field is wide open, so do like Professor Hoke and get inventing!

The impact of an actual vibrator, on the other hand, has been proven to be very real for many stressed-out ladies. Remember, as the advertisement states, the professor is “at home” at the National Hotel in York, Pennsylvania, on Tuesday and Wednesday. Hurry now before his appliances sell out for the holidays.